Understanding technical articles and books about movements of the shoulder blades can sometimes be confusing. This is in part because these texts use complicated terms without providing translations in everyday language or providing examples of how this information relates to exercise.

The BioMechanics Method has created a list of helpful terms and simple definitions (below) to help you better understand the movements of the shoulder blades. This information (along with the movement examples provided) will help you better understand how the shoulder blades should function during movement to avoid pain and reduce the likelihood of injury so you can design more effective corrective exercise programs.

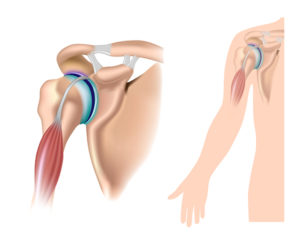

Movements of the Shoulder Blades

Anterior Tilt: When the top edge of the shoulder blade tilts down and forward and the bottom edge lifts up and away from the ribcage.

Elevation: When the shoulder blade moves upward on the ribcage (i.e., toward the head).

Depression: When the shoulder blade moves downwards on the ribcage (i.e., toward the waist).

Abduction: Can also be called Protraction. When the shoulder blade moves away from the spine.

Adduction: Can also be called Retraction. When the shoulder blade moves towards the spine.

Inward Rotation: When the bottom corner edge of the shoulder blade rotates down and in towards to the spine.

Outward Rotation: When the bottom corner edge of the shoulder blade rotates up and away from the spine.

Movement Examples

Movement Examples

Rowing: The shoulder blades should abduct and outwardly rotate as the arm reaches forward. As the arms pull the weight back the shoulder blades should retract and inwardly rotate back to the starting position.

(Note: Shoulder blade movement will change slightly as the arm raises, lowers or the width of grip is altered.)

Lat Pulldowns: The shoulder blades should outwardly rotate and elevate as the arm reaches upwards. As the arms pull the weight back down the shoulder blades should inwardly rotate and depress back to the starting position.

(Note: Shoulder blade position will also include adduction/adduction and anterior tilt if gripping cable handles where hands can come together and move apart and forward of body during motion.)

Push ups: The shoulder blades should retract and slightly inwardly rotate (depending on how wide the hands are placed apart) on the down phase of the push-up. As the arms push away from the body the shoulder blades should protract and slightly outwardly rotate.

(Note: Scapula movement will change if the position of the arm or hand placement is altered.)

If these movements of the shoulder blades are disrupted (or if the presence of musculoskeletal imbalances affects correct function of the shoulder blades during any movements), then problematic compensations can result leading to further dysfunction and pain and possibly injury (e.g., rotator cuff injury, etc.). Therefore, before you place yourself or your clients under the stress of dynamic exercise (such as those listed above), it is important to assess the condition and function of the shoulder blades and make assessments about the capabilities of the muscles surrounding the shoulder blades and whether they are prepared to move correctly.

Fitness, exercise and health professionals interesting in learning how to assess and correct the underlying causes of their client’s aches and pains with corrective exercise can choose to enroll in the industry’s highest-rated Corrective Exercise Specialist certification course from The BioMechanics Method. To learn more about this amazing program click on the image below.